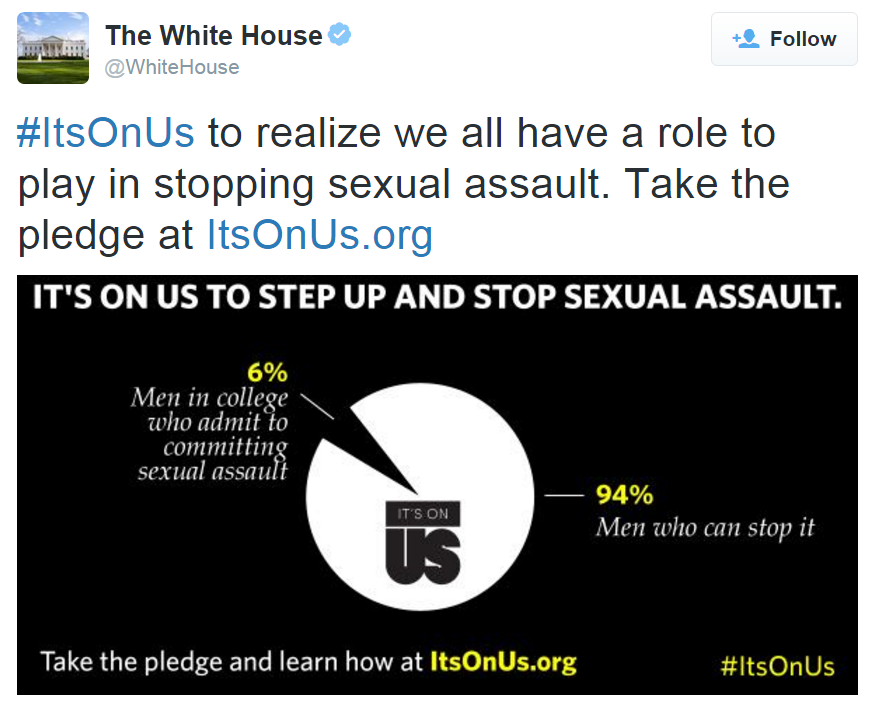

Having taught College Composition for 9 years now, I know that any time I ask students to include research I’ll get the same response: “So… like… statistics?” They’re the go-to. The first stop. And for some students, the final answer. Why though? Why do we see statistics as these great things that make our conclusions that much stronger and our points that much more relevant? If you’re asking me, and let’s just assume for a minute that you are, I think it has a lot to do with our understanding. Numbers are numbers. They are clear. Countable. Concrete. Though empathy and critical thinking are tough, nebulous concepts we have to work at, numbers are clean and easy to “get.” There’s a reason we learn them in our very first schooling experiences. In many ways, numbers help us understand our world and our place within it. A few weeks ago, I ran across some numbers that I couldn’t quite let go. I’m still puzzling over them and I’m wondering if maybe you can help me. The TweetOn September 22, 2015, The White House shared a simple chart and the tweet “#ItsOnUs to realize we all have a role to play in stopping sexual assault. Take the pledge at http://ItsOnUs.org.". Though the text of the tweet restates the mission of the It’s On Us campaign, the chart provides new information about college demographics. According to It’s On Us’ research, 6% of college males admitted to committing sexual assault, leaving 94% of college males capable of preventing the same. The campaign shows this breakdown with a stark pie chart in white on a black background with the It’s On Us logo placed inside the 94% portion of the pie. The chart is framed by “It’s on us to step up and stop sexual assault” on top and a link to the It’s On Us website and the It’s On Us hashtag at the bottom. By presenting this chart on the White House’s twitter account, the It’s On Us campaign is reminding the whole country of the issue of sexual assault on college campuses and specifically asking male college students to “step up” and “take the pledge.” The AttemptThough this tweet is brief, both because it’s a tweet and because of the minimalist presentation of their data, there’s a lot of persuasion packed in. One of the most subtle rhetorical moves in the White House’s tweet is concession. Jay Heinrichs, author of Thank You for Arguing, describes concession as more “Jedi knight than Rambo” (43-44). Heinrichs tells us concession allows the persuader to use their opponent’s arguments against them. For example, in this tweet, the It’s On Us campaign is the Jedi speaker, using the force of It’s On Us detractors’ most common counterargument against them. Often those who resist talk of the problem of sexual assault or the efforts to prevent it will wave off the issue by saying that not all men are violent and dangerous. Knowing their opponents (often males) will make this case, It’s On Us acknowledges only 6% of college men admitted to sexual assault and asks the remaining 94% to step up to prevent further assault. It’s On Us taking the strength out of the #notallmen dismissal really makes sense. In order for someone to dismiss this campaign now, they’d have to change approaches and come up with a new counterargument. This use of concession is very smart for the It’s On Us campaign, since a large part of their audience (college males) could respond defensively to the campaign if they feel they are being attacked. By conceding right out of the gate, It’s On Us is working to make sure that isn’t the case. The It’s On Us campaign actually does even more to cultivate what Cicero called the ideal audience (57). Heinrichs calls it “the ideal state of persuadability” to have your audience “attentive, trusting, and willing to be persuaded” (77). Though It’s On Us does not always face the ideal audience, they do their best to create it with this tweet. Most of their effort can be seen in terms of attention and willingness to be persuaded. First, It’s On Us gets their college-aged male audience’s attention by surveying them and tweeting about their findings. As we all know, audiences are most interested in themselves and the things that directly affect them. Second, It’s On Us gets on their audience’s good side by giving 94% of them a virtual high-five for not participating in sexual assault. By identifying them as the overwhelming majority and asking them to take the pledge, It’s On Us is showing the 94% they are already doing the right thing and could very easily do more by joining It’s On Us. This strategy reminds me of a department store door prizes. As long as you show up on a certain day, they’ll give you a free gift. Their hope, of course, is that you’ll then look around the store and buy something else while they’ve got you feeling happy and special. In the same way, It’s On Us is hoping to reach out to college males, congratulate them on being decent, and get them to support the campaign while they’re feeling good about themselves. This free praise may go over well in terms of getting their audience attentive and willing to be persuaded. Once It’s On Us gets their audience attentive and willing to be persuaded, they then have to give them an action worth taking. In this tweet, they do that through the use of patriotism. While we think of patriotism in terms of identifying with a country, Jay Heinrichs tells us we can feel patriotism towards any group we belong to, especially when that group is threatened by another group’s success (89). In this tweet, the group we’re to identify with is our own campus community. It’s On Us’ hope is that college males who value safety for their college community will see that 6% of college males as a threatening group and will pledge to step up. Using patriotism in this way provides a common enemy, anyone participating in or allowing sexual assault on college campuses. Heinrichs tells us pathos is more effective than logos or ethos for actually getting people to do something. By tapping into this sense of protectiveness over their campus communities, It’s On Us is motivating all their readers (college males and others involved on college campuses) to take the pledge and step up for their communities. The HitchOn the face of it, anticipating your opponents’ counter argument, drawing them to your side with praise, and then getting them to unite against a common enemy seems like it would move people directly from reading the tweet to pledging with It’s On Us. I could see how this strategy could be persuasive and I’ve seen some of my students respond well to it. I’ve also seen some students react with skepticism and I think they are right in doing so. The biggest mistake It’s On Us makes rhetorically is in assuming we will trust them blindly. The whole message of this tweet relies on the big gap between 6% and 94%. Between those who have admitted to sexually assaulting someone and those who can stop it. My students and I question these numbers though. How do they find these numbers? How many people didn’t admit to it but did take part? How much worse would the percentages be if people were honest? In fact, asking these questions is the point of college. Where is your research? Show me your steps. On what are you basing this conclusion? If every student left my class asking these questions, I’d nominate myself Teacher of the Year. Daydreams aside... Since the It’s On Us campaign is specifically targeting college students, they need to anticipate and answer these questions before they’re asked. A simple link to their research or mention of their study title would go a long way with this crowd. By showing their sources, It’s On Us would be demonstrating their trustworthiness and as Heinrichs would say, showing they know their craft (69). Right now, it's a good tweet for those who are willing to blindly agree. College students are rarely known for their blind trust though, so the campaign must support their claims about college students with credible evidence. As a composition instructor, this White House tweet is important to me and not just because it illustrates the importance of research and citation (thought it does an excellent job of that!). Even more important, I appreciate this tweet’s call to college males, who may not have been told that it is up to them to prevent sexual abuse on their campus. In a stage in their lives when peer pressure is arguably at its highest, knowing where the 94% lies is important.

We are all more likely to stand up for what is right if we know there is a crowd supporting us - whether that crowd is 94% of our peers or a slightly different It seems like a lot to ask for from one tweet, but I really think this short tweet and accompanying graph could make a big difference in campus safety here at GSU and across the country. If this blogpost has inspired you to check out the It's On Us campaign, their pledge, and how you can help, start with their website. You'll find everything you need there to see how you can help stop sexual assault on our campus.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Amanda J. HedrickStory collector, recipe enthusiast, educator, striving for a constant input and output of all things art and learning. Archives

September 2022

|